Many students aren’t initially quite how to set their GMAT performance goals and aspirations. Deep down, many struggle with an underlying question that sets their mindset and has a large influence on how well they might perform; does my performance on the GMAT depend more on a) how hard I work, or b) my IQ or natural test taking abilities?Indeed, the first belief that can very easily prevent you from reaching your potential on the GMAT is the belief that performance is, in large part, determined by IQ or natural test taking abilities. This just isn’t the case.

The GMAT is designed to measure your ability to succeed in business school, which means it is designed to test for quantitative, analytical, data interpretation, reading comprehension, critical thinking, problem solving, and writing skills. All of these skills can be developed with practice, which means that performance on the GMAT depends more on hard work than IQ or natural ability.

At this risk of sounding obvious, let’s explore why this belief is such a killer. Basically, the more you believe that the GMAT is a form of IQ test, the less incentive you have to prepare well before you take it. Few people believe it’s a pure IQ test, so almost everyone studies. But, studying for the GMAT, especially if you are working full-time and/or have a family, takes dedication, grit, and determination. If deep down, you think it’s a test of natural intelligence, you are far more likely to be just a bit less engaged, and slightly more likely to give up on a difficult problem. When you are less engaged with the material and spend less time struggling with it, you will learn less. It’s a simple, proven fact backed by lots of neuroscience research. To truly learn, you need to fully engage, push yourself, strive to improve, and believe that you can in fact improve with practice. There is in fact a psychological theory (with lots of scientific lab and real-world evidence to support it) that simply having a growth mindset (i.e., a belief that with practice and hard work your intelligence will improve) actually leads to improvement in academic performance over time. It’s a theory that both intuitively seems accurate and is scientifically supported.

One critically important point to mention is that GMAT skills tend to be skills that you develop in high school, college or graduate school, not just when you sit down and pop open a GMAT prep book. So, you might observe a friend who barely studied for the GMAT and scored a 730. This might be viewed as evidence that the GMAT must be testing something along the lines of IQ – how else could this person perform so well without studying?

Well, let’s consider one of MyGuru’s best tutors. He holds a B.S. in Mathematics and English from Indiana University, and scored a 760 on the GMAT without a large amount of studying. How? Well, because he had chosen a course of study in school that prepared him rigorously for the exact material (mathematics, reading comprehension, and writing) which appears on the GMAT. His GMAT prep had been happening for years and years. If you think you have lots of examples of people that excel on the GMAT without much studying, ask yourself what those people studied in school, and how recently they were in school. You might find that while they weren’t explicitly studying for the GMAT, they’ve been building skills in other ways for years. Even someone who tends to read a lot will tend to score better on GMAT reading comprehension questions. In fact, simply reading the Wall Street Journal or Economist more and quizzing yourself on the main idea and key assumptions is something we recommend to all of our GMAT students as a key part of the preparation process. It’s also one of the recommendations in our new book about preparing for standardized tests: Plan, Prepare, Perform.

Now, beliefs about the nature of the GMAT almost always lie somewhere on a continuum, not on either end. Few people would argue that the GMAT is purely an IQ test and can’t be prepared for. But, some believe this a little more or a little less. They have a more or less growth oriented mindset, and they might be looking for evidence in either direction when it comes to GMAT prep.

Things brings us to the second belief that might be holding you back, which is the belief that improvement in skill level, as measure by your practice GMAT scores, is a linear process. The process is often not linear.

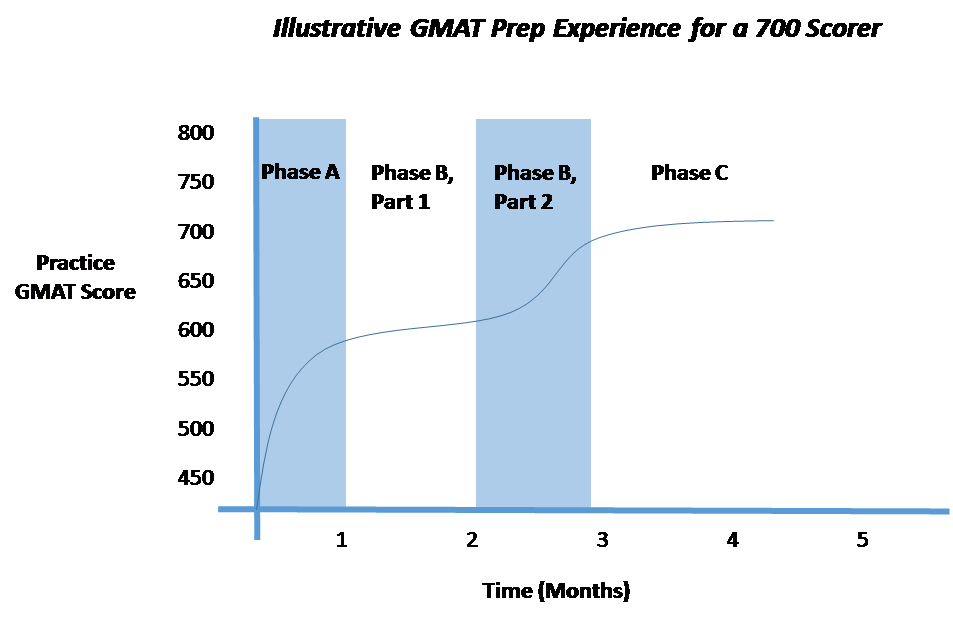

I tell most students that 10-12 weeks of study, let’s call it 3 months, is a reasonable amount of time to prepare for the GMAT. Let’s say you need to improve from a 550 to a 700 to get into your target school. If the process was linear, after about a month you could expect to score a 600 on a practice exam. After two months, a 650. Then, around the time when you are going to take the exam for real, you’d be scoring around 700. Oftentimes, though, that isn’t what happens, because the average relationship between amount of or time invested in prep and the results you see on practice tests isn’t linear. Instead, it often starts out as logarithmic, then becomes exponential, then reverts back to being logarithmic. See the graph below.

Here are some basic math terms to supplement the below discussion:

- Logarithmic = the rate of change slows over time (starts fast, then slows)

- Exponential – the rate of change increase over time, (starts slow, then speeds up)

In simple terms (although understanding the math lingo could be helpful for the GMAT):

- You start out fast, remembering basic, important math facts and getting the hang of simple test taking strategy, but eventually progress slows substantially (phase A in the above graph, which is a logarithmic area of the graph)

- Then, things get tougher, as you’ve bitten off all the “low hanging fruit” and need to start building skills that might be missing (on the GMAT, this means getting familiar with concepts such as rates of change, advanced algebra, probability, and number theory). This takes practice, and your score on practice tests might not be improving much for a long period of time (this is phase B part 2, the beginning of an exponential area of the graph)

- At some point, things start to “click.” You’ve built new skills, understand the various question types and common tricks, and being successfully answering more difficult questions, even very difficult questions, as you gain confidence and become creative and flexible. You’ve now entered the end of phase B, and as happened right at the beginning of your GMAT prep, your practice scores start to rise quickly)

- Finally, there’s typically a final phase, in which your progress slows and flattens, as illustrated by Phase C

Ok, fine. So, what’s the problem again?

The problem is that many students expect the relationship to be linear, and since they’ve planned on three months of study to eventually get a 700, and were seeing results early on, they are frustrated to be scoring almost 600 after a month and not much higher than 625 after 5-6 more weeks (perhaps 10 weeks in total at this point). They think they’ve done all they can do, and they might start thinking something along the lines of “well, I knew this was kind of like an IQ test anyway, I’ve reached my potential, which happens to be 625-650, not 700.”

You should fight the urge to think this way. Often times it takes a little while for new skills to develop, gel and result in better performance on GMAT practice tests. But once they do, your performance improves quickly.

Obviously, some people target a GMAT score of 550, others 650, and other 750, so the exact numbers here aren’t important. But, for a person targeting a 700, I all too often see them more or less “give up” or at least “become satisfied’ with a 625 or 650, because they’ve been studying for a while and aren’t seeing improvement, and this frustration is driven in part by the underlying belief that, if hard work matters, then the relationship between hard work and results will be linear. With an understanding of the above graph, that person would carry on, expecting a step change in performance to be coming around the corner soon, and continue to work towards that 700.

In other words, take a look at the above graph. When you’ve decided you’ve improved as much as you can (within reason, of course – notice that even in Phase C you might be able to improve 10-20 points with another two months of studying, which wouldn’t make sense to try to do), challenge yourself to ensure that you’ve reached Phase C.

Stopping your GMAT prep when you’re squarely in Phase B could mean you’re leaving 50-75 points of GMAT performance on the table.

Mark Skoskiewicz founded MyGuru, a boutique provider of 1-1 tutoring and test prep, and is the author of a forthcoming book on how to prepare for standardized tests: Plan, Prepare, Perform.